Theory of harmony

More information on the copyright for this drawing on the following link: Gertrud Grunow

As architects and urban designers we are “life directors” of spaces where people can live and make live different kind of scenarios. We have a responsibility in our designs to influence healthy, community friendly and life-style friendly environments. While it sounds very dreamy, on the other side of the mirror, architects often work in questionable conditions.

A great number of architectural studios and architectural education institutions cultivate routines and praxis of overtime, sleepless nights, low wages, high expenses, work for free while consuming high doses of caffeine, having a nutritiously poor diet and minimal physical activity. Contrary to the principles of harmony, balance and inclusivity we praise in our projects, in architecture as a profession, the mental and physical health of the architect is very often neglected. And we are used to that. We accept it.

There are exceptions. While I was researching the care for the physical and mental wellbeing of the students at the Bauhaus, I discovered that the students practiced breathing and concentration exercises to trigger creative expression. A significant principle of the Bauhaus was that “only a balanced, healthy individual can accomplish creative achievements”.

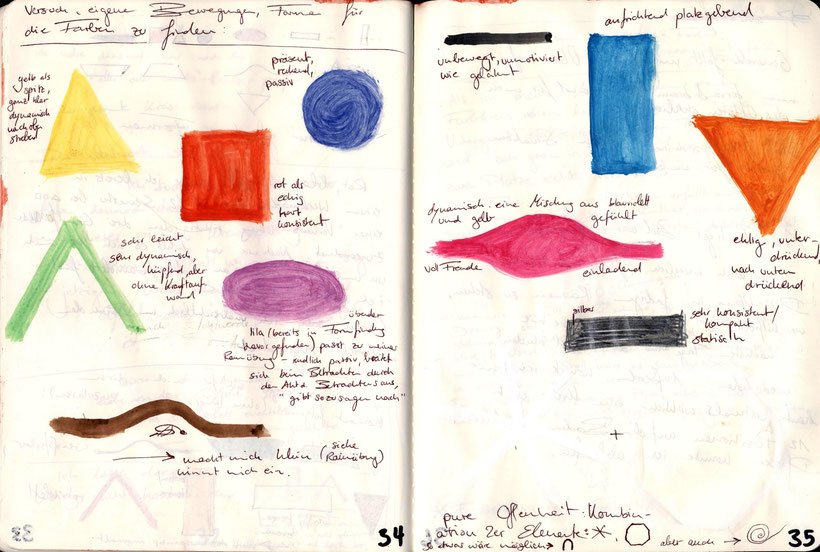

For example, in the period from 1920 and 1923, Gertrud Grunow was synthesising reform pedagogy with Asian meditation. In the subject Theory of harmony she taught students how to stabilise the body, mind and soul through sound, colour and movement. During her courses, the students got instructions how to reduce the emotional and physical tension, how to approach the relationship between body and soul in order to achieve physical and emotional harmony.

We need a new slowness of designing. One that allows us to take our breath. If we can’t breathe while designing, how are we supposed to create healthy environments? Now, take a moment and ask yourself: when was the last time you took space of stillness to reflect on who you are as a designer?

More information on the copyright for this drawing on the following link: Gertrud Grunow

Perhaps if you dedicate some of your time to ride on waves of stillness, we can start to raise the awareness of balancing mind, body and soul within our profession, as well as considering what alternatives we have in finding new approaches to health in architectural education and work.

On the topic of health in architecture, I would recommend you to check the following resources:

How Architecture builds a profession of stress: https://wellcomecollection.org/articles/XBdyexEAAKsb72Tb

Mental well-being and the architecture student: https://www.absnet.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Dissertation-Melissa-KirkpatrickV3.pdf

Work-related mental wellbeing in architecture: https://architectureau.com/articles/work-related-mental-wellbeing-in-architecture/

Survey: 25% of UK architecture students treated for mental health problems: https://www.theguardian.com/education/2016/jul/28/uk-architecture-students-mental-health-problem-architects-journal-survey

Како архитекти и урбани дизајнери ние сме режисери на простори каде луѓето можат да живеат и да создаваат живот преку различни сценарија. Носиме одговорност во нашето проектирање да влијаеме на здрави средини кои се отворени за различни заедници и животни стилови. Иако звучи многу сонувачки, од другата страна на огледалото, архитектите често истите тие проекти ги создаваат во дискутабилни работни услови.

Голем број на архитектонски студија и образовни институции негуваат рутини и пракси на прекувремено работење, непреспани ноќи, ниски плати, високи трошоци, бесплатна работа додека се конзумираат високи количини на кофеин, исхрана со ниска нутритивна вредност и минимална физичка активност. Спротивно на принципите за хармонија, баланс и инклузивност кои ги вреднуваме во нашите проекти, во архитектурата како професија, менталното и физичкото здравје на архитектите е често занемарено. И навикнати сме на тоа. Го прифаќаме.

Постојат исклучоци. Додека истражував образовни институции кои се грижат за физичкото и менталното добробитие на студентите на Баухаус, открив дека студентите често практикувале вежби за дишење и концентрација за да го инспирираат креативното изразување. Значаен принцип на Баухаус е дека “само балансирана, здрава индивидуа може да се воздигне креативно”.

More information on the copyright for this drawing on the following link: Gertrud Grunow

Како пример, во периодот од 1920 до 1923 година, Гертруд Грунов на своите часови ја синтетизирала западната педагогија со Азиската медитација. Во предметот Теорија на хармонија таа ги учела студентите како да го стабилизираат телото, умот и душата преку звук, боја и движење. За време на нејзините часови, студентите добивале инструкции како да ја намалат физичката и емотивната тензија, како да пристапат кон односот помеѓу телото и душата за да можат да постигнат физичка и чувствена хармонија.

Ни треба нова бавност на проектирање. Онаа што ќе ни дозволи да си земеме воздух. Доколку не можеме да дишеме додека проектираме, како треба да цртаме здрави средини? Сега, земи момент и прашај се: кога последен пат си зема мирен простор да рефлектираш кој/а си како архитект?

More information on the copyright for this drawing on the following link: Gertrud Grunow

Можеби ако си земете време да се пуштите на бранот на спокојството, можеме заедно да почнеме да ја зголемуваме свесноста за балнсирање на умот, телото и душата во нашата професија, додека истовремено размислуваме за алтернативи за здрави пракси и навики во архитектонското образование и работа.

Темата здравје во архитектонската професија е прилично опширна и би ви ги препорачала следниве ресурси:

How Architecture builds a profession of stress: https://wellcomecollection.org/articles/XBdyexEAAKsb72Tb

Mental well being and the architecture student: https://www.absnet.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Dissertation-Melissa-KirkpatrickV3.pdf

Work-related mental wellbeing in architecture: https://architectureau.com/articles/work-related-mental-wellbeing-in-architecture/

Survey: 25% of UK architecture students treated for mental health problems: https://www.theguardian.com/education/2016/jul/28/uk-architecture-students-mental-health-problem-architects-journal-survey